Smart Fishery Tracker™

The future of fish is uncertain. For the first time in history, fishers are faced with the possibility of being excluded from their historic fishing grounds — displaced for conservation and other economic opportunities. But, fishers see and touch more of the ocean than any other stakeholder and should be considered an important ally in ocean monitoring, management, and conservation. The eOceans® Smart Fishery Tracker™ was designed to help position fishers in this role, to effectively and efficiently improve their efforts, eliminate the barriers that lead to unreported and unregulated fisheries, and enable them to play a critical role in the management and conservation of our ocean.

The future of fish is uncertain. For the first time in history, fishers are faced with the possibility of being excluded from their historic fishing grounds — displaced for conservation and other economic opportunities. But, fishers see and touch more of the ocean than any other stakeholder and should be considered an important ally in ocean monitoring, management, and conservation. The eOceans® Smart Fishery Tracker™ was designed to help position fishers in this role, to effectively and efficiently improve their efforts, eliminate the barriers that lead to unreported and unregulated fisheries, and enable them to play a critical role in the management and conservation of our ocean.

Fishers have been the primary ocean explorers and knowledge holders throughout history. Photo: Erik Lukas, Ocean Image Bank.

A brief history — fish formed global economies

Throughout history, fishers have been the primary ocean explorers and knowledge holders.

For thousands of years, fishers fished without markedly depleting ocean health, but as fish became a commodity – to power global economies – fisheries rapidly expanded. While governments subsidized industrialized techniques to maximize exploitation efficiency and profit, they often dismissed local fishers' concerns regarding declining populations.

These concerns have often proved true decades later, necessitating these same governments to reduce quotas and implement moratoriums across diverse species groups with varying degrees of failure and success.

Future of fish is uncertain.

Today, the future of fish and overall ocean health is uncertain.

The future of fish is uncertain after centuries of misuse combined with growing climate change impacts and the fervent push to grow the ocean economy. For the last Photo: Ahmed Fareed, Unsplash.

After centuries of misuse combined with growing climate change impacts and the fervent push to grow the ocean economy, the ocean and its value to humans are expected to degrade rapidly if business-as-usual continues (Doney et al. 2009; Hoegh-Guldberg 2015; Oliver et al. 2018; Mendenhall et al. 2020). For these reasons, coastal countries are expanding ocean monitoring, management, and conservation strategies to balance ocean health with economic uses (Douvere 2008; Foley et al. 2010).

However, getting these decisions right is not trivial.

Ocean monitoring, management, and conservation needs fishers.

Fishers comprise one of the most diverse and largest ocean stakeholder/rightsholder groups by number, area they cover, and time spent at sea.

They see and touch more of the ocean than any other group. By all accounts, fishers are on the frontlines of ocean change, and, with few exceptions, their lives, livelihoods, and communities depend on fish populations that are abundant.

Thus, fishers should be considered an important ally in ocean monitoring, management, and conservation (Gutiérrez et al. 2011).

Yet, a history of misinformation, broken trust, and unsustainable practices (Worm et al. 2013; Agnew et al. 2009; Ward-Paige et al. 2013), has dissolved relationships and pitted fishers against other stakeholders, scientists, and decision makers (Pomeroy et al. 2007; Spijkers et al. 2018; Mendenhall et al. 2020).

Gathering perspectives.

To understand the contemporary situation, we deployed three approaches.

First, we reviewed available materials on fisheries written by scientists, managers, and fishers, including scientific and gray literature and online documentation (e.g., social media, blogs).

Second, we casually interviewed fishers, fisheries observers, non-fishers in fishing communities, managers, marine and social scientists, and non-governmental organizations that deal with fisheries. We also attended public events (e.g., conferences, town hall meetings) where fisheries-related regulations were discussed (e.g., marine protected areas, quotes, moratoriums). Our conversations covered 28 countries, but were primarily in Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and various Caribbean countries.

Third, we reviewed commercial fishing logbooks and analyzed large fisheries datasets to understand the value and limitations of the data that are collected by fishers, and worked with the fishers who collected the data to uncover their interests.

From these perspectives, we developed a series of analyses that comprise the Smart Fishery Tracker™ tool.

Fishers are influential, and increasingly marginalized.

Our investigations revealed that fishers are still generally regarded as influential in coastal communities, but that their role is in flux.

As discussions evolve about what activities are or will be permitted in the ocean, fishers are faced with the possibility of being excluded from historic fishing grounds for both conservation and economic opportunities (e.g., aquaculture, energy).

Fishers are also feeling targeted by increased fisheries monitoring, where they fear their data will be used against them and they object to the invasion of privacy.

Some fishing groups have become so distressed by these multi-pronged pressures that they have united within associations/societies to collect and process their own fisheries data to hold government scientists and managers accountable and make sure that their interests are upheld.

The Smart Fishery Tracker™

The Smart Fishery Tracker (Fig. 1) was designed for collaboration and privacy.

Figure 1. Example analysis from the Smart Fishery Tracker™. Analyses are found in the eOceans® dashboard and includes spatial and temporal trends of catch and bycatch, with reported animal conditions. For demonstration purposes, we show a few of the analyses performed for the Southwest Lobster Science Society, in Canada, using their fisheries data (shared with permission).

It is a suite of digital tools and analytics that equip fishers and fishing groups with timely, expert-developed analysis of their catch and bycatch data, along with other ocean patterns that interest them (e.g., illegal fishing, invasive species).

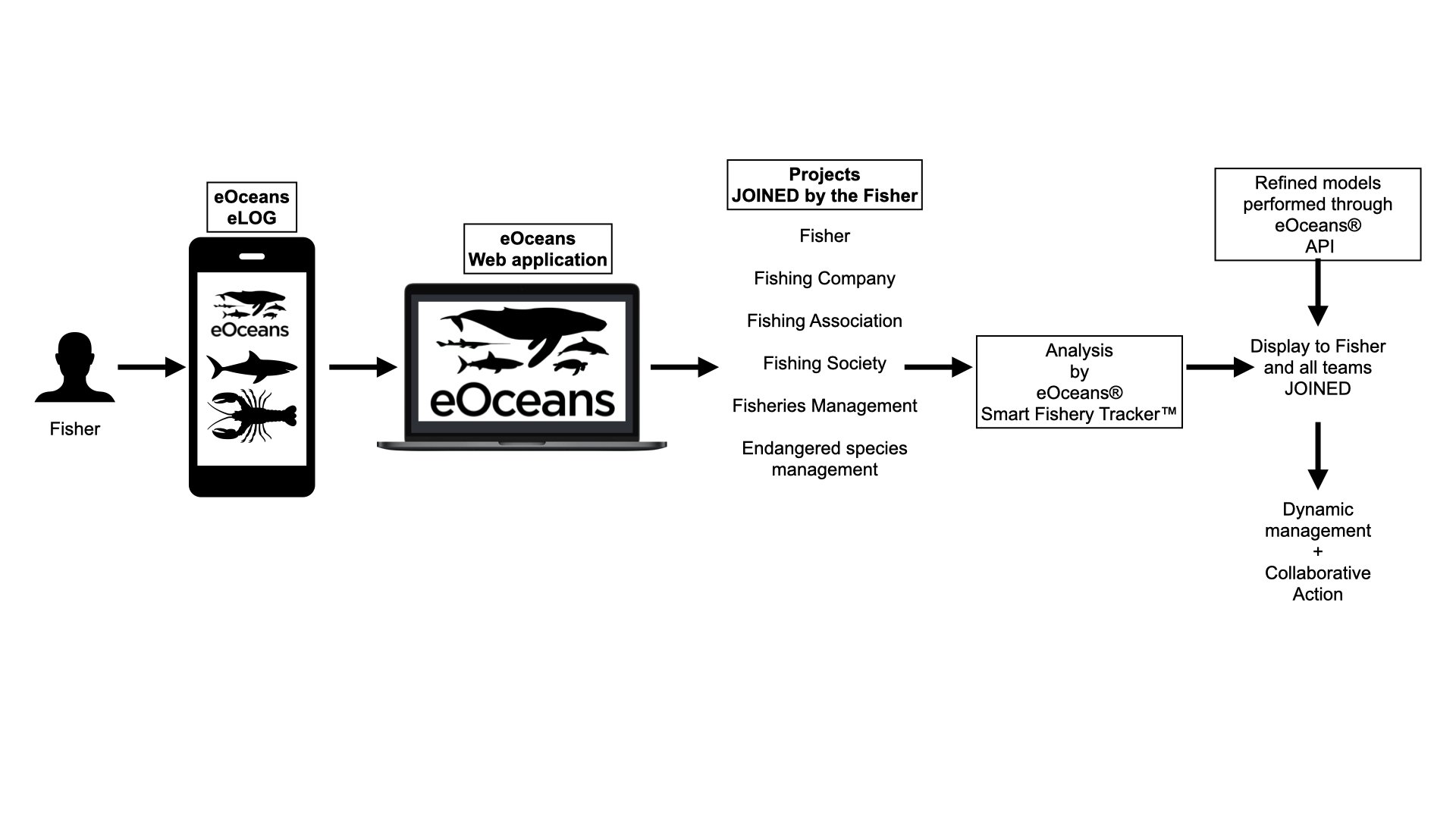

It uses the eOceans® platform (Fig. 2), where fishers and their collaborators interact with the platform in two ways.

Figure 2. Schematic of data flow in eOceans® Smart Fishery Tracker™. Fishers log catch, bycatch (species, number, condition) and other observations (e.g., whales, ghost gear, illegal fishers) in the mobile application while at sea. These data are saved in the eOceans® platform for their personal access. Data are streamed to supported projects, where they are analyzed and displayed for co-interpretation by project members.

The first is a mobile application (Fig. 3) where fishers can log their at-sea fishing effort, catch/bycatch, and other observations (e.g., whales, pollution), join projects to automatically share their data for analysis, and review and comment to help co-interpret the results.

Figure 3. Overview of the key components of the data entry part of the Smart Fishery Tracker™. The mobile app eLOG is used for data input by fishers. It automatically captures location, date, time, and other meta-data and the fisher or observer logs catch, bycatch, and other observations that feed the Smart Fishery Tracker™. The eLOG works offline and has precision of under 5 m.

The second is a web application where projects are launched and managed, and the results are reviewed and discussed. Projects can be created by anyone – fishers, fishing associations, managers, NGOs, scientists, consultants, etc. Projects only receive data from the fishers who have joined their project (i.e., it is an opt-in program).

The suite of analyses in the Smart Fishery Tracker combine summary and advanced modeling analysis with graphical and map summaries. The analyses include standardized assessments of catch, bycatch, and catch condition (e.g., size, maturity) using the data that are entered through the mobile application. It also includes analyses of the socioeconomic values of their ocean spaces (e.g., where and when they generally fish so as not to include exact sites) and anthropogenic threats (e.g., pollution, invasive species).

These results can be used for many purposes, from tracking quotas to voluntarily avoiding bycatch hotspots or moving gear that is near endangered species.

Scaling efforts and impact.

Because the ocean is complex and dynamic, the Smart Fishery Tracker™ not only helps fishers track any fishery or fishing area anywhere in the world, it also seamlessly works to track other ocean features in the same or adjacent areas.

Other eOceans® platform features that work well with the Smart Fishery Tracker™ include:

1) Community Channel, where fishers can broadcast interesting observations to their followers, which can be used to identify new, potentially invasive species, threats to the fishery, and bycatch that are to be avoided;

2) Comments tab, where fishers can comment on the results to help co-interpret their meaning or to improve data quality;

3) Timely Matters Notifications, where a text message can be sent to the team when a specific observation is logged, such as an endangered whale, that enables timely action (e.g., move gear);

4) Data Pipes, where external data sources, such as OBIS and ERDDAP, can piped into a project to extend baselines or to develop more advanced analyses (eg., fish with temperature and fisheries); and

5) other analyses and Trackers, like the MPA Health Tracker™, the Shark & Ray Tracker™, or the Blue Economy Tracker™, so fishers can easily and seamlessly participate in other dimensions of ocean tracking that matter to them.

A dent in IUU fishing.

Unreported and unregulated fishing often gets unfairly lumped in with illegal fishing and other criminal activities (IUU) (Song et al. 2020).

A lot of government scientists and managers are simply spread too thin with their workloads to manage all the fishers and fisheries. Therefore, a lot of fisheries simply don’t get monitored or regulated because of a lack of resources, not criminal activity.

The Smart Fishery Tracker™ offers a unique and affordable solution to effectively ending unreported and unregulated fishing since any fisher, in any fishery, anywhere in the world can now report their catch and, starting at less than $1000 per year, can have their analyzed for interpretation.

The future of fish.

The eOceans® platform has deployed different tools to identify and minimize errors, including using the metadata from the phone (e.g., location, date, time), flagging observation outliers, and an in-app field guide to help correctly identify species in the field.

This way, fishers and fishing teams can unite and get started tracking fisheries and fish populations, as well as other dimensions that may affect their fishery and access to fishing grounds — positively or negatively. Together, they can make informed decisions to benefit fish, fisheries, and fishers.

The Smart Fishery Tracker™ unites people to make informed decisions that benefit fish, fisheries, and fishers. Photo: Connor Holland, Ocean Image Bank.

eOceans — For the ocean. For us.

Ethics of ocean data: Caution for coastal communities and the growing blue economy

A rapidly growing number of organisations collect, distribute, and use ocean data from the backyards of communities that depend on the ocean. Use of these data could upend local ways of life. Below, I elaborate on the issues, share perspectives, and describe why and how the eOceans® platform was designed with ethics at its core.

A rapidly growing number of organisations collect, distribute, and use ocean data from the backyards of communities that depend on the ocean. Use of these data could upend local ways of life. Below, I elaborate on the issues, share perspectives, and describe why and how the eOceans® platform was designed with ethics at its core.

Aquaculture has been touted as a solution to feeding the growing human population. It also has a history of degrading ecosystems, native species, and displacing communities. Innovators, investors, stakeholders, and rightsholders need to be informed and working to drive a successful blue economy that supports ocean health, wealth, equitable access, and community wellbeing. Photo: Bob Brewer.

Examples for context.

What if… an ocean tech company placed an array of sensors that collected data that were used to identify the next aquaculture site, which diminished ocean health and displaced historical users of the ocean space?

What if… a tourist scuba diver shared their observations in a free (nothing is free!) mobile app (there are many!) and those data were sold or shared with poachers that targeted species?

What if… a scientist published environmental data in an open source repository that were then used to place a wind farm without consulting locals?

What if … marine animal first responders collected observations of endangered species and their threats (e.g., whale entanglements, strandings, ship collisions) and those data weren’t analysed or used to mitigate future threats?

What if… an organisation published maps of ocean bathymetry, including pinnacles that contain high abundances of fish, and those maps were made available to poachers to target prime fishing locations?

What if… an ocean ‘restoration’ company and government decided to build a ‘restoration’ site in a socially or biologically significant site (e.g., where surfers surf) to offset damage done elsewhere and that ‘restoration’ destroyed the native habitat and value?

These scenarios are real.

They highlight the urgent need for caution and new approaches to cross-sector collaboration and input when collecting and distributing ocean data.

An explosion of data.

There has been a recent explosion of ocean tech companies, researchers, governments, and NGOs tapping into the rapidly growing ocean economy and blue economy by collecting and distributing ocean data.

Buoy-, ROV-, Robot-, Camera-, Censor-, Satellite-, Measurement-, Software-, Community-, Data-as-a-service organisations collect and transfer data about the ocean to businesses, governments, researchers, and others who use the data for various reasons.

These data stream from the backyards of communities that depend on the ocean. Communities that have evolved to value their ocean spaces for traditional, cultural, recreational, and commercial purposes. But, most stakeholders and rightsholders are not made aware of the data being collected and few fully understand the potential risks.

Having detailed ocean datasets that contain high resolution, accurate, standardised, accessible, and timely data is necessary for understanding and making informed decisions about ocean uses, but there are significant pitfalls that need to be considered.

The number of sensors and robots carrying sensors to collect and distribute ocean data is growing rapidly. Governance, or even conversations about governance, on who can and should be able collect or access these data is still in its infancy. Photo credit: Hanson Lu

(Very) Brief Primer on Ethics.

In my experience, few people outside of academia consider the ethics of ocean data. Data breaches and tech companies selling our personal data may have accustomed us, as individuals, to easily dismiss the risks associated with ocean data. These risks, however, could be far reaching and unforeseen.

Fortunately, there are many existing guidelines to help direct the ethical collection and use of ocean data.

Relevant to ocean data, ethical considerations generally fall into human, animal, and environmental categories.

When working with humans, protocols state that participants must be fully informed about the goals and risks and consent to participating, and must not mislead or waste their time. Therefore, any project that collected data from local knowledge holders or coastal communities that was used to harm them without them understanding the risk and still providing their consent is unethical. Communities need to be aware of and consent to the risks, including those that extend to their livelihoods, social or cultural values, and rights to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.

When working with animals, protocols stipulate that the benefits must outweigh the risks and the number of animals and their degree of suffering should be minimised. Collecting data about animals and not using those data to their fullest extent, such as to minimise the number of animals that suffer (e.g., entanglements, ship collisions) is unethical. Data should be leveraged to help protect future animals from undue harm.

Environmental ethics generally aim to protect and sustain biodiversity and ecological systems. Providing sensitive ocean data to exploitative or uninformed users, especially in areas without fully developed marine spatial plans and enforcement capacity, is unethical. Care is needed to ensure the humans, species, and ecosystems are carefully considered.

The numerous examples presented at the beginning of this essay demonstrate the fallout that can occur when the ethics of ocean data have not been fully considered.

Perspective matters.

Motivations for collecting and using ocean data vary widely. Academics, inventors, businesses, communities, governments, and the public have different mindsets regarding ocean data, and many will exploit the data for nefarious reasons. Effectively balancing value with risk in ocean data requires consideration by diverse stakeholders.

My perspective comes from nearly 30 years as an ocean science researcher, teacher, entrepreneur, tech founder, inventor, ocean diver and explorer, and someone who has interviewed thousands of ocean stakeholders in over 38 coastal countries. My research and teaching experience required human and animal ethics approvals. I’ve also been in many positions to recommend decisions that would affect local communities, including placing “artificial reef” structures and recommending changes to marine policies, protected areas, fisheries, and pollution.

What if… an ocean 'restoration' company and government decided to put a restoration site at a socially significant site (e.g., where surfers surf) to offset a development somewhere else and it destroyed the site for current users or species? Photo credit: Alistair MacRobert

Status quo of ocean data.

In developing the policies that would dictate how the eOceans platform collects and distributes data, I met with hundreds of ocean organisations and decision makers to understand existing data policies. I found that data policies varied widely but generally fell into four main approaches:

1) Open access and freely available.

2) Do not share because they own the data.

3) Cannot share because they don’t maintain a database.

4) Cannot share because the data were collected under ethical permissions that prohibit sharing without permission.

Costs of each approach.

Each approach has different values and risks.

1) Open access and free to use.

Open access and free to use ocean data has been pushed by many academics and international programmes (e.g., OBIS, CIOOS, IOOS, GBIF) because it is seen as “fundamental for improving the ways we observe the oceans”. Open and freely available data, following FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), saves time and resources and allows scientists, decision makers, businesses, and communities to have data they may not have otherwise.

Open access data, however, can be especially risky to local stakeholders and rightsholders. Although some repositories have protection for endangered species, targeted species and special places remain vulnerable to exploitation in open data. The risks are particularly high in areas where marine spatial planning and enforcement are not fully developed. Wildlife poachers and other exploitation companies exploit open data to identify and target coveted resources.

Similarly, open data generated by fishers or local knowledge holders (e.g., participatory or citizen science) would expose special places and species. And, there is additional risk with local knowledge being made open because it diminishes the possibility of re-consent and puts researchers in an ethical conundrum.

2) Do not share because they own the data.

Companies, academics, and governments often don’t share data — they are gatekeepers.

The reasons for gatekeeping vary.

They can include corruption and greed, but it can also be more simple and/or legitimate.

Some don’t make their ocean data open or freely available because they provide data-as-a-service — it’s their business model. Others, especially smaller organisations or one-off research projects, don’t have datasets that were designed to fit into larger sampling strategies and they have self-created methods that aren’t easily shareable.

Others, however, don’t share data because they want proprietary access. This type of gatekeeping is particularly problematic when the work involves “helicopter science” or participatory/citizen science, where the data, information, and knowledge leave the communities from where they were collected. Additional challenges arise because participants and communities have wasted their efforts and resources with little benefit.

3) Cannot share because they don’t maintain a database.

A lot of small-medium organisations, despite collecting data, do not actually have databases. In some cases this is understandable because it is arduous and expensive to create, maintain, and use databases, especially if data science is not a priority. Not using the data, however, has ethical dilemmas.

Marine animal first responders are a good example. They collect essential data, typically from phone hotlines, about marine animals that have died or are in distress (e.g., stranded, entangled, injured) and need assistance. Their priority is helping the animal in need so most don’t maintain databases. If they did it right, however, they could have powerful datasets that could help mitigate animal suffering by identifying and averting threats.

Education-focused NGOs and companies (e.g., voluntourism) are another example. They send people — volunteers, citizen scientists, tourists — into the field to ‘collect data’. Most never move the data off paper log sheets and a few stated they don’t care because their goal is to make people ‘feel’ engaged. The ethical dilemma here is multi-fold because not only are the data not being used (e.g., for conservation, marine spatial planning, science) but the participants are being misled into believing they are collecting data for a cause and are wasting their time if they could have joined another organisation that would actually use their data.

4) Cannot share the data because the data were collected under ethical permissions that prohibit sharing without re-consent.

This is the barrier that was relevant to my own research. I worked at a university and would collect data about animals and ocean spaces using the observations made by humans. Depending on the project, I needed both human and animal ethics approvals. My permission to use these data only extended to what participants consented to, mainly the paper that would be produced at the end.

This put my own work into an ethical dilemma where I, with the help of local experts, described the patterns of threatened species (e.g., sharks). After many species were listed on CITES other researchers wanted to use the data to understand how the listing helped populations. Further investigations could help decision makers further refine or enforce policies and reduce the number of animals and communities that continue to suffer from illegal, undocumented, and unregulated fishing. Repeating the survey would waste a lot of time and resources, but using the data for this purpose would not be possible without re-consent.

Diverse ocean stakeholders, rightsholders, businesses, technology, and governments are competing for ocean spaces. Wind farms, for example, are displacing historical fisheries and animal migration routes. Photo: Christine Ward-Paige

Ethics at the intersection.

While ocean tech appears to be a blue ocean opportunity under the umbrella of growing the so-called ‘blue economy’, caution is needed throughout the phases of research and development, business model creation, investment, scaling ‘solutions’, policy creation, etc.

On the other hand, coastal communities also have an important role to play. It is important that they know what data are being collected, who has access, and possibly develop their own policies around the collection, distribution, and uses to ensure they receive maximum benefit and minimal risk. They should also understand and be able to advocate for decisions that align with their values and livelihoods.

Open source data and maps, including bathymetric maps that show all the ocean’s pinnacles – where fish aggregate – enable industrial fishers and poachers to easily target and rapidly overfish prime fishing locations. This is particularly problematic in areas or countries with limited enforcement capacity. Photo: Chris Davis.

eOceans cares.

Our mission at eOceans is to be the company that helps rebuild ocean health and wealth by bringing people, data, and knowledge together in real-time for actionable decisions.

Our metrics of success are:

✅ bountiful marine species

✅ healthy marine ecosystems, and

✅ thriving coastal communities

We spent years researching and developing the policies that dictated the design and function of the eOceans platform. Although we’ll always look for ways to improve, the goal is to maximise benefit and minimise risk for coastal communities, ecosystems, and species.

We are also extremely interested in fostering relationships and partnerships with other organisations that deploy ethical approaches — the more there are to work with, the better.

What eOceans does.

The eOceans platform empowers and enables local knowledge holders — scientists, fishers, tourism operators, recreational explorers, etc. — to quantitatively tell their stories.

Ocean observations are logged in the eOceans mobile app and automatically analysed at all spatial scales. Researchers and organisations can use the eOceans platform to gather observations to track any marine species, protected areas, issues, fisheries, poaching, social values, etc. Photo: eOceans

To break silos and facilitate collaboration across locations and perspectives, eOceans harnesses the approach of F.A.I.R. data while also adhering to the concepts of privacy, consent, and data sovereignty. The data that come into the eOceans mobile app or that are exported through our reports are standardised following international standards (i.e., Darwin Core, WoRMS) that facilitate the sharing of biodiversity data. Instead of making the data open and freely available like others, the eOceans platform itself is open and free. Users can contribute as much data as they like, on any species, any issue, anywhere in the world’s ocean or connected freshwater ecosystems for free.

eOceans staff scientists use the eOceans data and platform to track global trends in a few dimensions (e.g., sharks, whale strandings, pollution) and the platform can be used by other researchers and organisations to conduct their work at the spatial scales they need.

To enable collaboration, transparency, and trust eOceans users:

✅ Own their data

✅ Decide how their data can be used

✅ Assist with the interpretation of results

✅ Facilitate knowledge distribution, and are an

✅ Integral part of the action dialogue

The data cannot be removed from the platform for external purposes without the explicit permission of the data contributors. This way participants are empowered to decide how their data are used and can be part of the risk mitigation strategy.

Additionally, all the data within each project are automatically analysed by the eOceans platform and the results are displayed in near real-time so contributors can always see what’s happening in their communities with their contributions.

Finally, for further transparency, the eOceans platform has a dedicated space for projects to declare their ethics statements and acknowledgements (e.g., funders) so that all project leaders can transparently share any potential conflicts of interest with their contributors.

Call-to-Action

Initiate productive conversations! Innovators, entrepreneurs, investors, organisations, and governments in the data collection, storage, distribution and use space should engage with each other, and with local knowledge holders and coastal communities, to develop and deploy ethical strategies for ocean data to support an equitable blue economy without jeopardising coastal communities.

Let us know! We’d love to hear about the data that have been collected in your ocean. Have there been mostly benefits, or also costs?

Getting this right is not trivial, so the more detailed conversations we can have with broad audiences and perspectives, the closer we can all get to a healthy ocean and equitable ocean spaces.

eOceans — For the ocean. For us.

We’d love to have you join our global community of ocean explorers tracking the ocean in real-time:

Join eOceans on your mobile device (iOS, Android) or desktop. Use the mobile app to log what you see when you are under, on, or next to the ocean or a connected water body.